To Shake or Not to Shake: The Truth about Salt, Blood Pressure and Weight

by Gwyn Cready, MBA, and Ted Kyle, RPh, MBA

Fall 2014

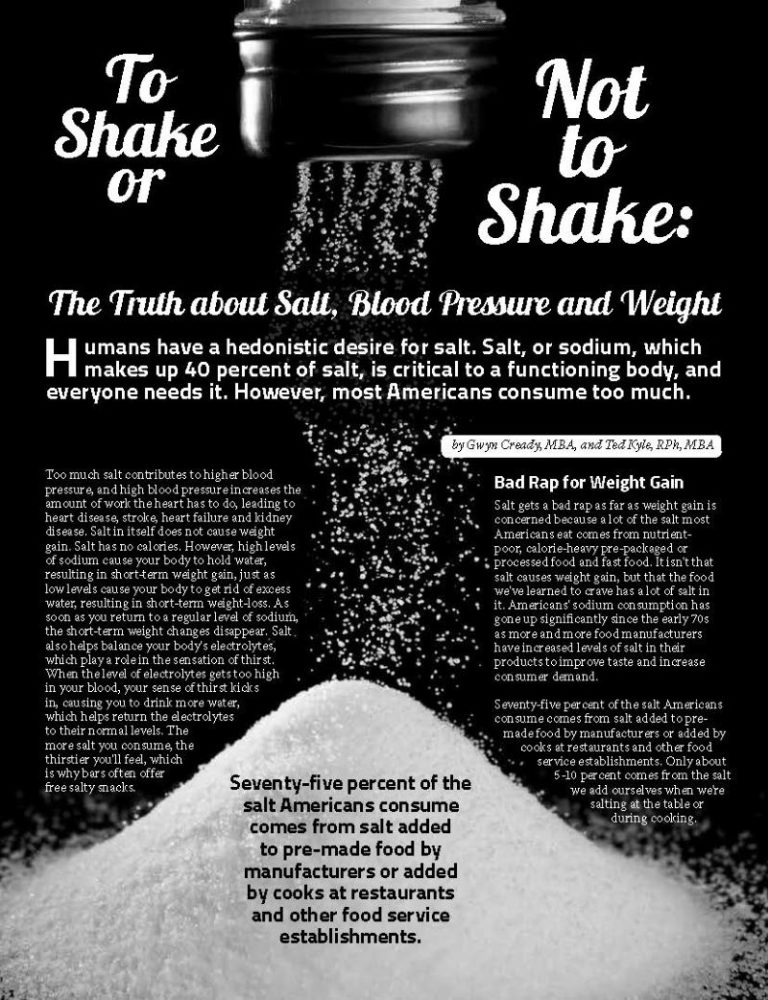

Humans have a hedonistic desire for salt. Salt, or sodium, which makes up 40 percent of salt, is critical to a functioning body, and everyone needs it. However, most Americans consume too much.

Too much salt contributes to higher blood pressure, and high blood pressure increases the amount of work the heart has to do, leading to heart disease, stroke, heart failure and kidney disease. Salt in itself does not cause weight gain. Salt has no calories. However, high levels of sodium cause your body to hold water, resulting in short-term weight gain, just as low levels cause your body to get rid of excess water, resulting in short-term weight-loss. As soon as you return to a regular level of sodium, the short-term weight changes disappear. Salt also helps balance your body’s electrolytes, which play a role in the sensation of thirst. When the level of electrolytes gets too high in your blood, your sense of thirst kicks in, causing you to drink more water, which helps return the electrolytes to their normal levels. The more salt you consume, the thirstier you’ll feel, which is why bars often offer free salty snacks.

Bad Rap for Weight Gain

Salt gets a bad rap as far as weight gain is concerned because a lot of the salt most Americans eat comes from nutrient-poor, calorie-heavy pre-packaged or processed food and fast food. It isn’t that salt causes weight gain, but that the food we’ve learned to crave has a lot of salt in it. Americans’ sodium consumption has gone up significantly since the early 70s as more and more food manufacturers have increased levels of salt in their products to improve taste and increase consumer demand.

Seventy-five percent of the salt Americans consume comes from salt added to pre-made food by manufacturers or added by cooks at restaurants and other food service establishments. Only about 5-10 percent comes from the salt we add ourselves when we’re salting at the table or during cooking.

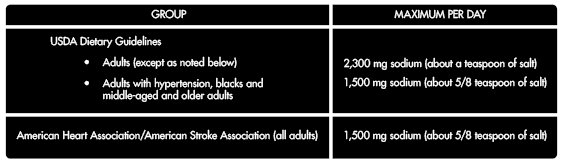

The Dietary Guidelines for Americans currently recommends no more than 2,300 milligrams of sodium per day (about 1 teaspoon of salt) for most Americans and only 1,500 milligrams per day (about 5/8 of a teaspoon) for individuals with hypertension, blacks, and middle-aged and older adults. Americans, on average, consume about 50 percent more than the recommended amount—about 3,400 milligrams per day. Other groups have recommended a maximum of 1,500 milligrams of sodium for everyone.

The FDA’s Role in Regulating Salt

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) classifies salt as a GRAS (Generally Recognized as Safe) ingredient, whose use in food does not require FDA approval. The FDA does require that food manufacturers state sodium content on their labels, and it sets criteria for how the claims “low sodium” and “reduced in sodium” can be used.

In 2007, the FDA held a public hearing on the agency’s policies regarding salt in food and solicited comments from the public about future regulatory approaches. The agency was also a sponsor of a high profile report released by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) in 2010 that recommended various strategies to reduce the amount of sodium Americans consume, including actions food manufacturers, public health professionals, consumer educators and government agencies should take. The report recommended that the FDA set mandatory national standards for the sodium content in foods. The recommendation was not that sodium should be banned as an additive, but that approved sodium levels in manufactured food and food served in restaurants should be gradually reduced throughout time.

According to the IOM report:

“It is important that the reduction in sodium content of foods be carried out gradually, with small reductions instituted regularly as part of a carefully monitored process. Evidence shows that a decrease in sodium can be accomplished successfully without affecting consumer enjoyment of food products if it is done in a stepwise process that systematically and gradually lowers sodium levels across the food supply.”

The report argues that the voluntary approaches taken to date on the part of food manufacturers and restaurants “have not been sufficient,” and it concludes that “without major change, hypertension and cardiovascular disease rates will continue to rise, and consumers, who have little choice, will pay the price for inaction.”

The FDA is reviewing the IOM recommendations, but, to date, has not acted on them.

What You Can Do

Most experts agree it’s important for Americans to take steps to lower their sodium intake. Here are five tips from the National Kidney Foundation for things you can do to lower yours:

- Make reading food labels a habit. Sodium content is always listed on food labels. Sodium content can vary from brand to brand, so compare and choose the lowest sodium product. Certain foods don’t taste particularly salty but are actually high in sodium, such as cottage cheese, so it’s critical to check labels.

- Stick to fresh meats, fruits, and vegetables rather than their packaged counterparts, which tend to be higher in sodium.

- Avoid spices and seasonings that contain added sodium, for example, garlic salt. Choose garlic powder instead.

- Many restaurants list the sodium content of their products on their Web sites, so do your homework before dining out. Also, you can request that your food be prepared without any added salt.

- Wait it out. You can learn to adjust to eating less salt. It typically takes about six to eight weeks on a low-sodium diet to get used to it. After that, you’ll actually find that some of your favorite salty foods, like potato chips, taste too salty to you.

In short, shake if you must, but being a well-informed shaker can help you improve your health.

About the Authors:

Ted Kyle, RPh, MBA, is a pharmacist and health marketing expert and is also Chairman of the OAC National Board of Directors.

Gwyn Cready, MBA, is a communications consultant with more than 20 years of healthcare policy and brand marketing expertise as well as an award-winning romance novelist. You can visit her at www.cready.com.

by Sarah Muntel, RD Spring 2024 Spring has sprung, bringing sunnier and warmer days! For many, this…

Read Articleby Sarah Ro, MD; and Young Whang, MD, PhD Fall 2023 Mary, a postmenopausal woman with a…

Read Articleby Rachel Engelhart, RD; Kelly Donahue, PhD; and Renu Mansukhani, MD Summer 2023 Welcome to the first…

Read Article