Shame Campaigns – Do they work?

by Rebecca Puhl, PhD

Winter 2014

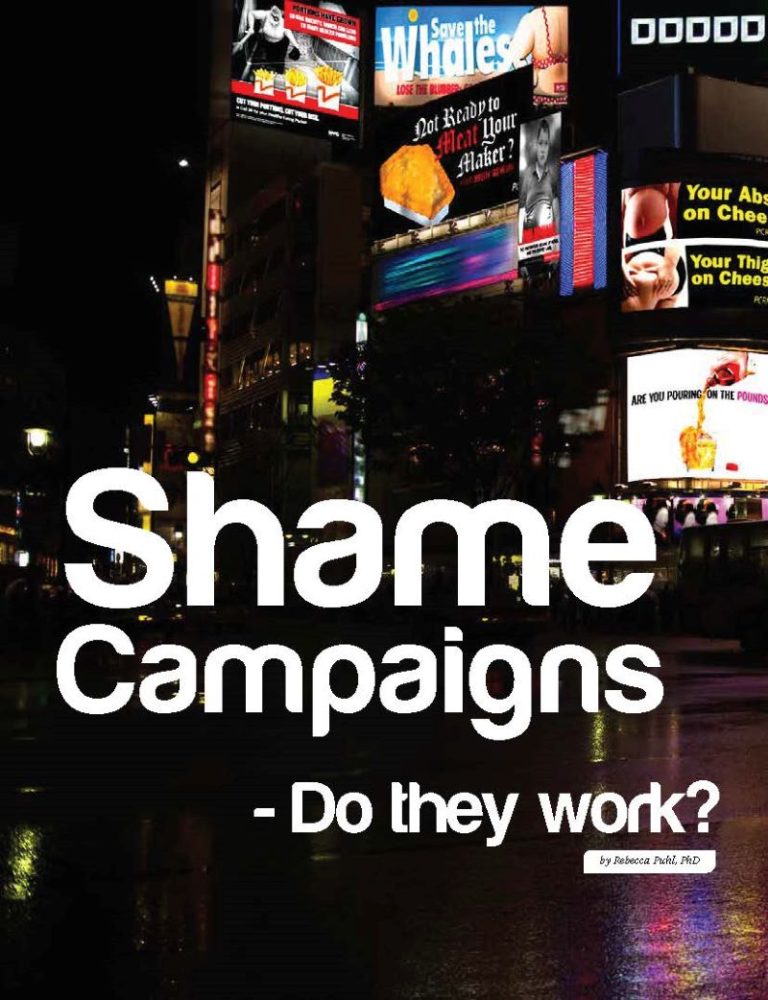

As part of national and state efforts to address obesity, many mass media campaigns have emerged throughout the country encouraging Americans to improve their diet and exercise more.

You have likely seen television commercials, billboards, or magazine ads sponsored by different health organizations promoting obesity prevention messages. These campaigns often focus on the importance of reducing portion sizes and soda intake, eating more fruits and vegetables, and increasing physical activity. As an example, First Lady Michelle Obama’s Let’s Move! Campaign has been widely publicized and broadly embraced across the United States, which aims to encourage healthy eating and activity behaviors in children.

Shock-Tactics

While most of these campaigns are initiated from positive intentions to improve public health, some anti-obesity campaigns have instead been criticized for shaming and stigmatizing individuals affected by obesity. As an example, in 2011, the Children’s Health Care of Atlanta Campaign to address childhood obesity in Georgia publicized billboards and commercials portraying youth with excess weight with “warning” captions such as “Stocky, Chubby, and Chunky are Still Fat” and “Fat Kids Become Fat Adults.” Despite being the target of public criticism for promoting shame and stigma toward families affected by obesity, these kinds of shock tactics are often defended by campaign organizers as being necessary to increase public attention to the issue, and from misperceptions that shame and stigma may actually provide an incentive for people to lose weight.

Gathering Public Opinion

As a researcher who has studied weight stigma for more than a decade, I was concerned that these types of campaigns would do more harm than good. We know from considerable research evidence that experiencing weight stigma can worsen psychological and physical health, impair weight-loss efforts, and potentially lead to increased weight gain. In addition, given that so many people with excess weight already suffer from stigma and prejudice, and are frequently made to feel ashamed of their bodies, the potential harm that could come from public health campaigns using shaming tactics is a legitimate concern. I was also surprised to learn just how little research was being done by health organizations to test their messages and approaches before they launched their obesity-related campaigns. In an effort to address this, my research team at the Rudd Center conducted two nationwide studies to see what Americans really think of different anti-obesity campaigns.

Specifically, our aim was to examine public perceptions of obesity-related health campaigns that were recently publicized throughout the U.S. In our studies, we presented people with a series of obesity-related campaigns to look at (including those that had stigmatizing content and those that were more neutral), and we asked them to evaluate each campaign on a number of different characteristics. For example, we asked participants to what extent each campaign instilled feelings of motivation to improve their health, whether they felt able and confident to make health behavior changes that were promoted by the campaign, whether they felt the campaign reinforced negative stereotypes about persons affected by obesity, and whether they felt the campaign content (both pictures and words) was appropriate. Our findings revealed some important insights:

-

-

- First, obesity-related campaigns that were rated to be stigmatizing were no more likely to instill motivation for improving lifestyle behaviors than campaigns rated as more neutral.

- In addition, stigmatizing campaigns were also rated as inducing less self-confidence to engage in health behaviors promoted by campaigns, and viewed to have less appropriate visual content compared to neutral campaigns.

-

These findings also remained consistent across different segments of the public (regardless of a person’s own body weight). Importantly, these findings challenge the idea that stigma is an acceptable or necessary approach to take in efforts to address obesity. It also indicates that shaming and stigmatizing approaches are less effective than non-stigmatizing campaigns to encourage health behaviors.

When we looked more closely at the types of obesity-related campaigns that the public favored and felt motivated to improve their health behaviors, we came across another important finding: campaigns that were rated to be most motivating for improving health behaviors were those that did not even mention the word “obesity,” and in most cases made no mention of body weight at all. These were campaigns that instead focused on promoting specific health behaviors, such as eating more fruits and vegetables, or replacing sugar sweetened beverages with water; behaviors that all Americans can engage in to improve their health, regardless of their body size.

What Does this All Mean?

What these findings tell us, is that weight stigma undermines the ability to effectively communicate with Americans about obesity and health. People feel much more motivated and empowered to make healthy lifestyle changes when campaign messages are supportive and encourage specific health behaviors. In contrast, when campaigns communicate shame or stigma, people feel less motivated and have lower intentions to change their health behavior. Our research findings also suggest that campaigns don’t need to focus on obesity in order to promote healthy eating and exercise behaviors. This kind of approach could go a long way in helping to reduce weight stigmatization.

Removing the emphasis on obesity, and instead focusing on healthy behaviors that everyone can engage in regardless of their body weight, can help reduce blame and shame directed at persons affected by obesity and support all individuals in their efforts to be healthy.

Conclusion

Clearly, there is much work that needs to be done to ensure that media campaigns are truly empowering and supporting people as they take steps to improve their health behaviors, rather than alienating persons affected by obesity and instilling shame and stigma. This also holds true for the way that we talk about obesity in other settings, such as in schools with children, and with healthcare providers and their patients.

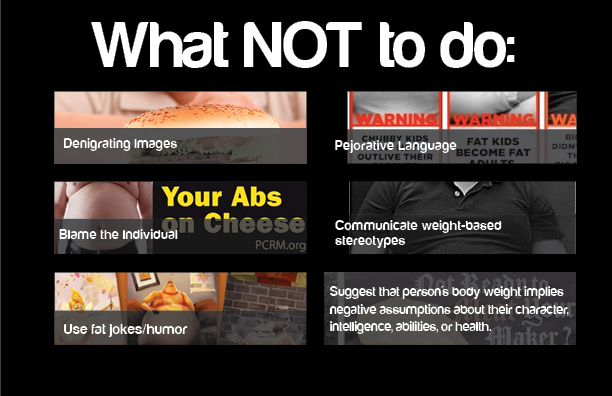

As a starting point, our research highlights strategies that can lead to a more careful and thoughtful consideration of approaches and messages that are used to communicate about weight-related health. Summarized below, are the “Do’s” and “Don’ts” that can serve as general guidelines for obesity-related campaigns, but these also apply to the way that we talk about weight and health as health providers, educators, and even as parents. We all need to promote a positive and productive dialogue about weight-related health without any stigma or shame, and with plenty of support and empowerment.

About the Author:

Rebecca Puhl, PhD, is the Deputy Director at the Rudd Center for Food Policy & Obesity at Yale University. For more information about Dr. Puhl’s work, please visit www.yaleruddcenter.org.

References:

Puhl, R.M., Peterson, J.L., Luedicke, J. (2013). Public reactions to obesity-related public health campaigns: A randomized trial. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 45, 36-48.

Puhl, R.M., Peterson, J.L., Luedicke, J. (2012). Fighting obesity or obese persons? Public reactions to obesity-related health messages. International Journal of Obesity. doi:10.1038/ijo.2012.156

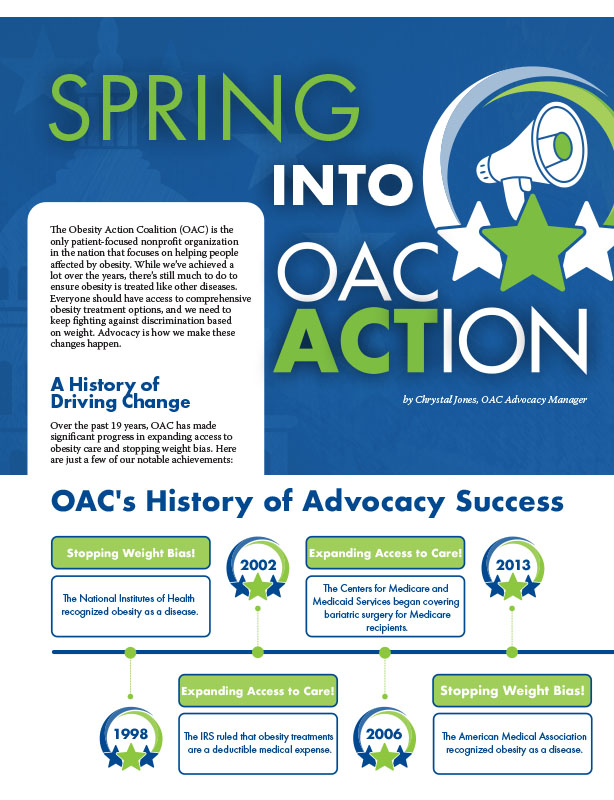

by Chrystal Jones, OAC Advocacy Manager Spring 2024 The Obesity Action Coalition (OAC) is the only patient-focused…

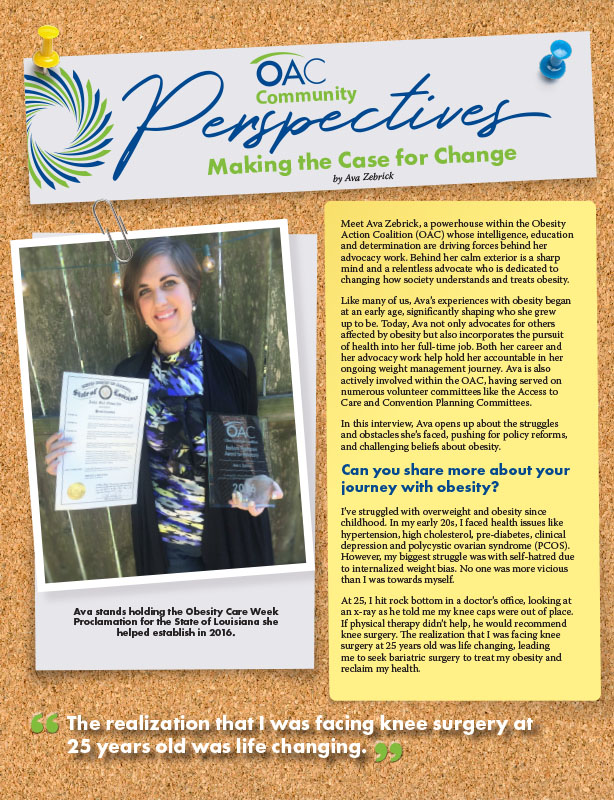

Read Articleby Ava Zebrick Spring 2024 Meet Ava Zebrick, a powerhouse within the Obesity Action Coalition (OAC) whose…

Read ArticleThe OAC is honored to welcome three new members to the OAC National Board of Directors. Jason Krynicki,…

Read Article