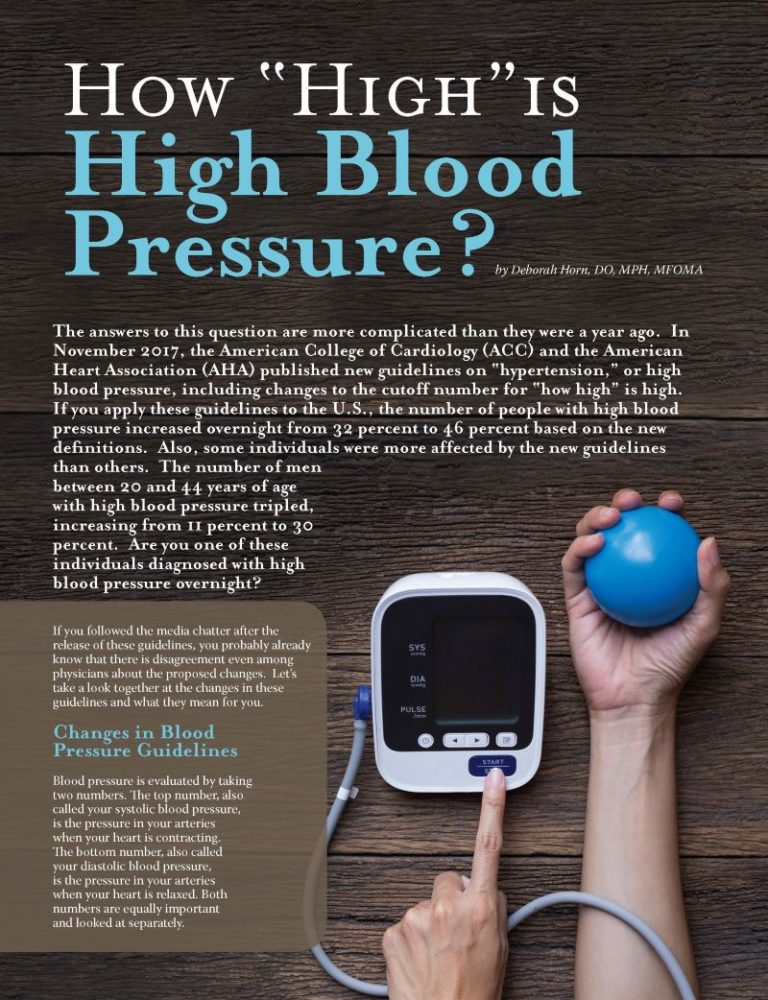

How “High”is High Blood Pressure?

by Deborah Horn, DO, MPH, MFOMA

Spring 2018

The answers to this question are more complicated than they were a year ago. In November 2017, the American College of Cardiology (ACC) and the American Heart Association (AHA) published new guidelines on “hypertension,” or high blood pressure, including changes to the cutoff number for “how high” is high. If you apply these guidelines to the U.S., the number of people with high blood pressure increased overnight from 32 percent to 46 percent based on the new definitions. Also, some individuals were more affected by the new guidelines than others. The number of men between 20 and 44 years of age with high blood pressure tripled, increasing from 11 percent to 30 percent. Are you one of these individuals diagnosed with high blood pressure overnight?

If you followed the media chatter after the release of these guidelines, you probably already know that there is disagreement even among physicians about the proposed changes. Let’s take a look together at the changes in these guidelines and what they mean for you.

Changes in Blood Pressure Guidelines

Blood pressure is evaluated by taking two numbers. The top number, also called your systolic blood pressure, is the pressure in your arteries when your heart is contracting. The bottom number, also called your diastolic blood pressure, is the pressure in your arteries when your heart is relaxed. Both numbers are equally important and looked at separately.

How Did the Guidelines Change?

Based on previous guidelines, “normal” blood pressure is considered less than 120 mmHg of systolic pressure and less than 80mmHg of diastolic pressure. Your doctor may have referred to this as a blood pressure less than 120/80. If your blood pressure falls between 120-139 mmHg systolic or 80-89 mmHg diastolic, you are diagnosed with “prehypertension.” Finally, a blood pressure of greater than or equal to 140 systolic, 90 diastolic is considered high blood pressure or hypertension.

Under the newly-proposed guidelines, a normal blood pressure is still less than 120/80. However, there is no longer a category of “prehypertension.” In fact, this category was broken into

two parts:

- Elevated blood pressure

- A new earlier diagnosis of Stage 1 hypertension

A blood pressure of 120-129 systolic and a normal diastolic blood pressure of less than 80 is considered “elevated blood pressure.” Stage 1 hypertension was redefined as any blood pressure greater than 130 systolic or greater than 80 diastolic. Previously, both of these numbers would have been considered “prehypertension.” This explains why with these new cutoffs, so many more people have a diagnosis of hypertension instead of prehypertension.

In summary, the diagnosis of hypertension was essentially lowered by 10 points for both of your blood pressure numbers. The authors of the proposed changes site studies that demonstrate increased risk of cardiovascular disease at these lower blood pressures as the reason for lowering the threshold for diagnosis.

Confused About What to Do? You Aren’t Alone.

Even though many major medical organizations have endorsed these new guidelines, there is no consistent agreement among all of your physicians. The American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) has not endorsed the new guidelines. They have recommended that family physicians and their patients stick to the last-updated guidelines of the Joint National Committee (JNC) from 2014 called JNC8, which we covered in the beginning of this article.

They indicated their reasons for not endorsing the new guidelines were that they were:

- Heavily based on the new SPRINT study

- Lacked enough evidence and discussion of risks to justify intensifying treatment

Additionally, the family medicine and internal medicine societies jointly published their own guidelines in January 2017, which are specific to adults older than 60 and conflict with the newly-proposed guidelines.

So What Should You Do?

First and most importantly, if your blood pressure is regularly above 120/80, start a conversation with your healthcare provider. If you choose to follow the new guidelines with your healthcare provider, it may change how early you decide to use medications to control your blood pressure.

Here are the basics to understand and discuss with your physician based on the newly-proposed guidelines:

- If you fall in the elevated blood pressure category, you should begin lifestyle changes to lower your blood pressure. Make sure to get it re-checked in three to six months.

- If you fall in the Stage 1 hypertension category, it becomes a little more complicated. Remember, this is blood pressure between 130-139 systolic or 80-89 diastolic. It only requires one of these numbers to be diagnosed with hypertension. If one number is elevated, then you must assess your risk for heart disease to make a decision about treatment.

- If your 10-year risk of heart disease or stroke is less than 10 percent, you should also begin to make lifestyle changes to improve your numbers.

- If your 10-year risk is more than 10 percent, or you have known heart disease, diabetes or chronic kidney disease, you might consider both lifestyle changes and a medication to lower your blood pressure. You should also have it re-checked in one month.

- Finally, if your blood pressure is 140+ systolic or 90+ diastolic, the new guidelines recommend:

- Healthy lifestyle changes

- Beginning two medications to lower your blood pressure

- Having your blood pressure re-checked in one month

This is a major change from previous guidelines, where a single medication would have been started first. In addition to medication, what other important actions should you consider taking? In other words, what falls under healthy lifestyle changes?

Measuring Your Risk

So how do you calculate your 10-year risk? You use the Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease (ASCVD) Risk Calculator. Go to cvriskcalculator.com.

Answer the questions and the program will give you your risk score. You will need your most recent cholesterol lab results as well as a recent systolic blood pressure number.

This is where most guidelines and healthcare providers can agree. Consider the Top 10 Healthy Lifestyle Changes List on page 54 for ways to tackle increased blood pressure head on!

Top 10 Healthy Lifestyle Changes

- Evaluate your blood pressure yearly.

- Get an accurate reading. This means no smoking, caffeine or exercise within 30 minutes of checking your blood pressure.

- Make sure the blood pressure cuffs at the clinic and at home are the correct size. A cuff that is too small will give artificially high readings, and a cuff that is too large will give artificially low readings.

- Check your blood pressure at home. Home readings are more accurate than clinic readings.

- Look for a cause. Most diagnoses of hypertension are what we call “essential hypertension.”

In other words, the cause is unknown. However, there are some secondary causes of high blood pressure such as kidney disease, abnormal thyroid function, drugs and alcohol – just to name a few. - Lower your salt intake.

- Reduce your weight. For every 2.2 lbs. you lose, your blood pressure will decrease 1mmhg. This means with a 20 lb. weight-loss, you could lower your blood pressure by 10 points. This change could be enough to keep you off of anti-hypertensive medication.

- Reduce your alcohol intake.

- Get active! Try to squeeze-in at least 150 minutes of cardiovascular activity per week, plus three bouts of strength training.

- Make a plan with your healthcare provider and follow through.

Conclusion

It will take several years to see how clinicians respond to these guidelines, to see if they are widely adopted and to eventually change how hypertension is treated. The most important thing is to be an educated patient, ask questions and make decisions together with your healthcare provider. It’s your health, and you need to have a plan that you can agree on and commit to long-term.

About the Author:

Deborah Horn, DO, MPH, MFOMA, is the President of the Obesity Medicine Association and Clinical Assistant Professor in the Department of Surgery at The University of Texas McGovern Medical School at Houston. She is the Medical Director for the UTHealth Center for Obesity Medicine and Metabolic Performance. Dr. Horn was also the recipient of the OAC’s Healthcare Provider Advocate of the Year award – an award given to a healthcare provider who is a tireless advocate for patients, the OAC and the cause of obesity.

by Nina Crowley, PhD, RD (with Inspiration from Shawn Cochran) Winter 2024 Dating, no matter your age,…

Read Articleby Sarah Ro, MD; and Young Whang, MD, PhD Fall 2023 Mary, a postmenopausal woman with a…

Read Articleby Rachel Engelhart, RD; Kelly Donahue, PhD; and Renu Mansukhani, MD Summer 2023 Welcome to the first…

Read Article