Food Labels – A Primer

by Jacqueline Jacques, ND

Spring 2007

If you are trying to eat a healthy diet and make good food choices, you will often get the advice: “become a label reader.” This is said in reference to the Nutrition Label found on virtually all foods sold in grocery stores in the United States.

Food labels are required by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) so that consumers can make an informed choice about the food they eat. When you know how to read them, you can understand valuable information about the ingredients in a food, its nutritional value as part of your diet and much more.

Nutritional labels on food are required by the FDA under the Food, Drug and Cosmetics Act and are regulated by the Office of Nutritional Products, Labeling and Dietary Supplements. The regulations set forth by this office literally regulate almost everything on a food label such as:

- What specific ingredients are called

- How the information is presented graphically

- What size type needs to be used

- How to use descriptive terms like “low,” “reduced” and “free” for fat, salt and calories

What foods have to be labeled?

These days, most foods sold in your grocery store are required to have some sort of label. The obvious exceptions are fresh fruits and vegetables and fresh cuts of meat or fish. Foods like sandwiches made in the grocer’s deli and those sold in bulk bins are also not required to be labeled.

Other foods that are exempt form labeling include:

- Foods sold in restaurants, hospital cafeterias and airplanes or sold by food service vendors (including vending machines)

- Food shipped in bulk – that which may be shipped to a restaurant for food preparation

- Medical foods

- Plain coffee, tea and spices

- Very small business – provided they inform the FDA and meet the criteria for this exemption

What should you look at when you look at a label?

Most people never get past the front of a food label when they are shopping – and that is what most manufacturers hope for. The front of a label is generally a modified ad for the food – maybe a picture that suggests a way to eat the food, catchy information like “low fat” or “part of a healthy diet,” and perhaps a slogan that is familiar to consumers as part of a bigger advertising campaign.

If you are a health-conscious shopper, the front of a label generally tells you very little of what you need to know. There are, however, a few things that are required to be present in this area of the label under FDA guidelines. These things include the name of the food and the quantity of the product in the container (ounces, grams, etc.).

In some cases, the manufacturer also must describe the form of the food – meaning they should tell you if the milk is skim or whole, the cheese is sliced or shredded or the pineapple is sliced or in chunks, etc. Virtually everything else is there by the choice of the manufacturer.

Turn the package over!

If you really want to know about a food, the front of the label doesn’t tell you what you need to know most of the time. The best place to start looking on a food label is the area – usually on the back or side of the package – called the Nutrition Facts Box. (If you are looking at a dietary supplement, this will be called a Supplement Facts Box.)

The Nutrition Facts Box

If you know what to look at, the Nutrition Facts Box actually provides a lot of information.

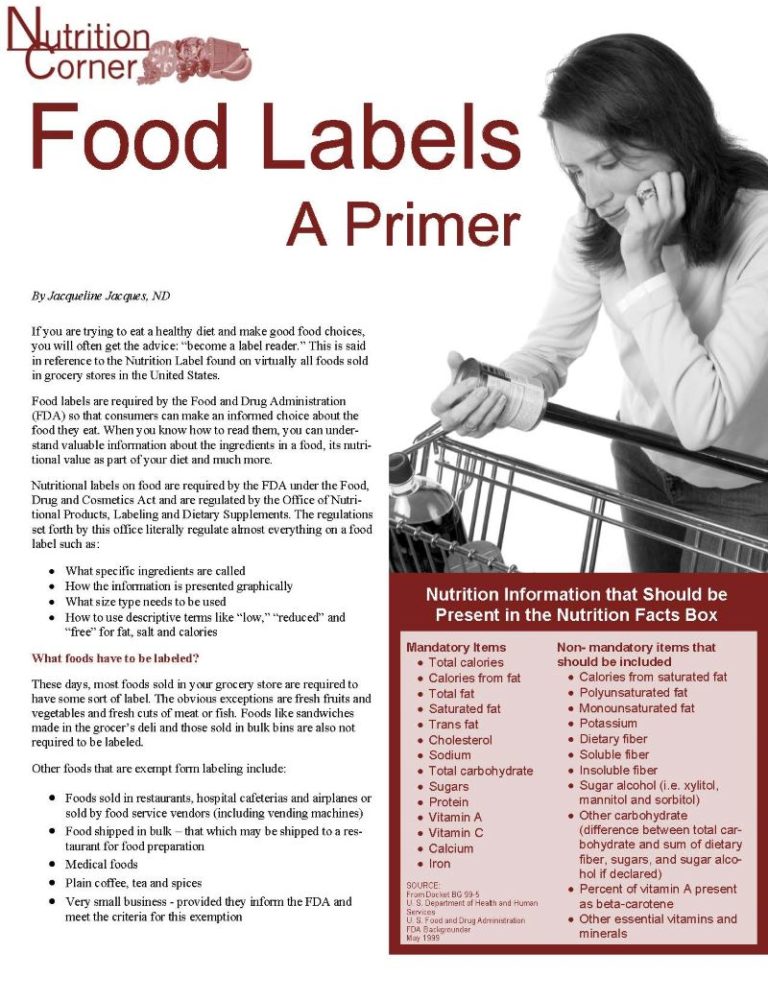

Nutrition Information that Should be Present in the Nutrition Facts Box

Mandatory Items:

- Total calories

- Calories from fat

- Total fat

- Saturated fat

- Trans fat

- Cholesterol

- Sodium

- Total carbohydrate

- Sugars

- Protein

- Vitamin A

- Vitamin C

- Calcium

- Iron

Non- mandatory items that should be included:

- Calories from saturated fat

- Polyunsaturated fat

- Monounsaturated fat

- Potassium

- Dietary fiber

- Soluble fiber

- Insoluble fiber

- Sugar alcohol (i.e. xylitol, mannitol and sorbitol)

- Other carbohydrate (difference between total carbohydrate and sum of dietary fiber, sugars, and sugar alcohol if declared)

- Percent of vitamin A present as beta-carotene

- Other essential vitamins and minerals

From the top of the box, you can start by looking at the serving size and the number of servings in a container. For products like bread, where the serving is usually one slice, this is typically easy to understand. For foods that don’t come in neat portions, consumers often do not use the serving size that the manufacturer recommends.

A great example is cereal. For many cereals, the serving size is 1/3 to 1/2 cup. That’s about a medium handful for most adults – and it doesn’t even come close to filling your cereal bowl. When pouring cereal, many of use three to four times the “serving” size. Same goes for foods like juice, pasta, chips, crackers, nuts, ice cream and other things where the serving size may differ a lot from what most people eat.

Two examples that I find bothersome are bottled drinks and nutrition bars. Many bottled drinks (from juice to soda) and packaged bars that look like single servings are actually 1 ½ to 2 servings per container. So, if you eat the entire contents of the package, you need to multiply the calories, fat content, etc by 1.5 or 2 to know what you are actually eating.

Everything else in the Nutrition Facts box is based on a single serving of the product – not on the amount that you typically eat. As you move through the box, keep this in mind. If you are trying to limit calories, fat, salt (sodium) or cholesterol, you can now much more easily know how much you are getting. If you want to make sure you get enough protein or fiber every day, you can see that as well.

Finally, you can also use the box to know how much iron, calcium, vitamin A and vitamin C you are getting each day. Other nutrients such as B-vitamins, vitamin E, D, K, and most minerals are not required, but can be listed voluntarily by the manufacturer.

You also see some percentages (%) in the Nutrition Facts box. These percentages tell you that for the listed nutrients how much of the Recommended Daily Value you get with a serving of that food. The Daily Value (DV) is the suggested amount of a nutrient (a vitamin, mineral, protein, fat, fiber or carbohydrate) that you should get each day. The Percent Daily Value (% DV) is the amount of that nutrient you should get based on an assumed calorie intake. For all nutrients, if they provide 5 percent or less of the DV, the food is low in that nutrient; if they provide 20 percent or more, they are high in that nutrient.

The FDA (Food and Drug Administration) generally assumes an intake of 2,000 calories for an average adult. Optionally, the manufacturer can show you percentages based on an intake of 2,500 calories as well. Also voluntary, but commonly shown, are the number of calories per gram of fat, carbohydrate and protein.

The Ingredients

The Nutrition Facts box is helpful, but the information in it is still limited. Foods are also required to have a complete listing of all the ingredients that they contain. This is required for all foods that have more than one ingredient. Usually this information is listed directly below or adjacent to the Nutrition Facts box. Ingredients are listed by weight.

While fewer ingredients don’t always make a healthier food, it is not uncommon to find that foods with long, complicated ingredient lists contain more additive, more fillers and more non-nutritional ingredients.

By reading this list carefully, it can help you to compare not just the simple nutrition facts in the box, but also the quality of your food. You might be amazed when you start to compare foods like catsups, breads, soups and more just how much variation there is for individual types of foods.

Allergens

The newest label regulations require specific information for ingredients that have been identified as potentially harmful allergens. The allergens that must be declared on food labels are:

- Milk

- Eggs

- Fish (e.g., bass, flounder, cod)

- Crustacean shellfish (e.g., crab, lobster, shrimp)

- Tree nuts (e.g., almonds, walnuts, pecans)

- Peanuts

- Wheat

- Soybeans

Manufacturers can declare the source of the ingredient directly in the ingredient list, or they can place this information in a separate statement following the ingredient list. (This will usually be preceded by the phrase “This product contains…”) While wheat is on this list, many medical authorities have commented that gluten is not, and perhaps should be. The FDA is currently reviewing the criteria for adding gluten to this list as well as looking to clearly define “gluten-free.”

Nutrient Content Claims and Health Claims

It is becoming increasingly common for manufacturers to market health claims about their food. Whether it is margarine that helps your heart, cereal that lowers cholesterol or simply something that is “healthy” compared to the other choices on the shelf. You might be surprised at how regulated this language is by the FDA.

A nutrient content claim is one that tells you that compared to a similar food, the food from brand X is lower in something (like fat or sugar), free of something (like sodium or cholesterol) or provides a better than average source of a nutrient (like calcium or protein). Virtually every term from “light” to “high” has a strict definition that manufacturers must meet to use the term, or they risk serious penalties and fines.

Actual health claims for foods are extremely limited. To date, there are only 12 that the FDA has allowed, though they are considering others. In addition, there are two approved claims based on authoritative statements from scientific bodies that are allowed. One is for whole grains, heart disease and cancer and states: “Diets rich in whole grain foods and other plant foods and low in total fat, saturated fat, and cholesterol may reduce the risk of heart disease and some cancers.”

The other is for potassium, high blood pressure and stroke, and reads: “Diets containing foods that are a good source of potassium and that are low in sodium may reduce the risk of high blood pressure and stroke.”

How to Get More Information about a Food

One final thing that is required on all food labels is contact information. Food manufacturers and distributors are supposed to provide at least their name, address (if they are unlisted), city, state, country (if outside the U.S.) and zip code. While not required, many now provide a phone number and/or a Web site. If you have a question about a product that you can’t find on the package, it can never hurt to ask at the source.

In Conclusion

Food labels may look complicated, but once you begin to look at them regularly you will start to see that the information they provide is useful in maintaining a healthy diet. If you are new to reading and comparing labels, allow yourself some extra, unhurried time at the market to read and compare.

To obtain more consumer information about reading and using food labels, contact the FDA at (888) 463-6332.

About the Author:

Dr. Jacqueline Jacques is a Naturopathic Doctor with more than a decade of expertise in medical nutrition. She is the Chief Science Officer for Catalina Lifesciences LLC, a company dedicated to providing the best of nutritional care to weight-loss surgery patients. Her greatest love is empowering patients to better their own health. Dr. Jacques is a member of the OAC Board of Directors.

SOURCE:

From Docket BG 99-5

U. S. Department of Health and Human Services

U. S. Food and Drug Administration

FDA Backgrounder

May 1999

by Sarah Muntel, RD Spring 2024 Spring has sprung, bringing sunnier and warmer days! For many, this…

Read ArticleEating disorders can be a concern or question for many who are along the journey to improved…

View VideoWhy we crave certain foods can be difficult to understand. Between the different types of food cravings…

View Video