Fill ‘Er Up – A Look at Gastric Banding Fills

by Lloyd Stegemann, MD, FASMBS

Winter 2011

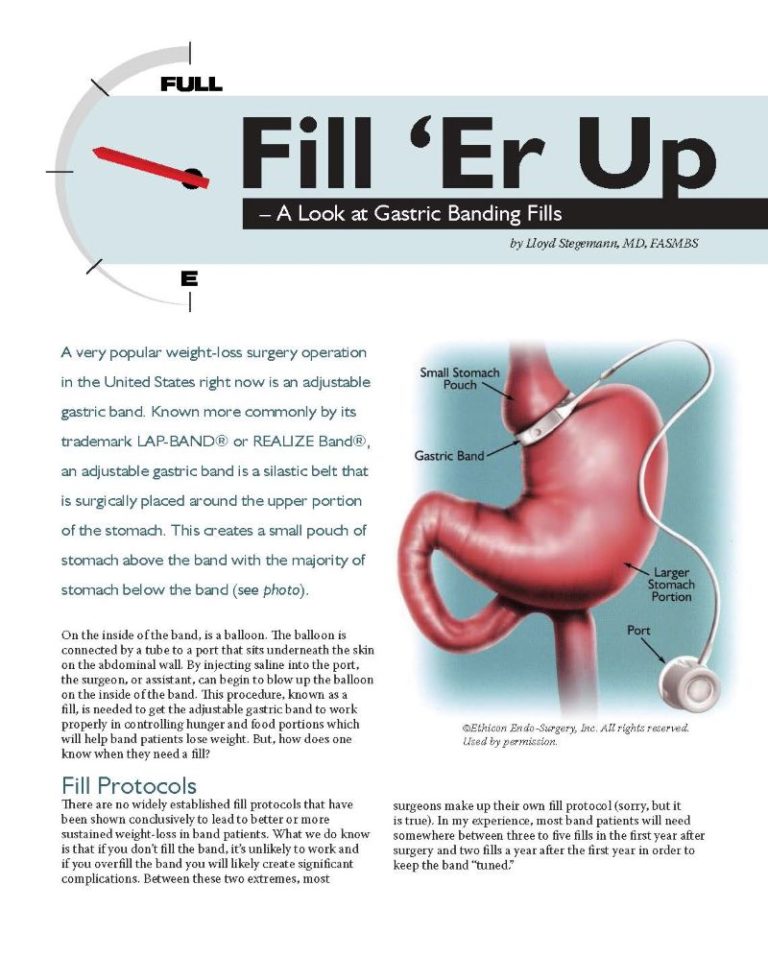

A very popular weight-loss surgery operation in the United States right now is an adjustable gastric band. Known more commonly by its trademark LAP-BAND® or REALIZE Band®, an adjustable gastric band is a silastic belt that is surgically placed around the upper portion of the stomach. This creates a small pouch of stomach above the band with the majority of stomach below the band (pictured right).

On the inside of the band, is a balloon. The balloon is connected by a tube to a port that sits underneath the skin on the abdominal wall. By injecting saline into the port, the surgeon, or assistant, can begin to blow up the balloon on the inside of the band. This procedure, known as a fill, is needed to get the adjustable gastric band to work properly in controlling hunger and food portions which will help band patients lose weight. But, how does one know when they need a fill?

Fill Protocols

There are no widely established fill protocols that have been shown conclusively to lead to better or more sustained weight-loss in band patients. What we do know is that if you don’t fill the band, it’s unlikely to work and if you overfill the band you will likely create significant complications. Between these two extremes, most surgeons make up their own fill protocol (sorry, but it is true). In my experience, most band patients will need somewhere between three to five fills in the first year after surgery and two fills a year after the first year in order to keep the band “tuned.”

Do I need a fill?

When I see a band patient, here are the things I consider when deciding if the patient needs to have a band fill:

Hunger Control

I think hunger control is paramount to achieve weight-loss. Hunger is a primal driving force in mankind and if people are hungry, they will eat. I ask each of my patients, “How many times a day do you get hungry?” Good hunger control, in my opinion, is when someone gets hungry two to three times a day and they aren’t searching for food between meals. Most band patients will get hungry somewhere between 10 am to noon and again somewhere between 5 pm to 7 pm. Hunger will vary from day to day, but my main concern is that people can get through the day without constantly thinking about food.

The next question I usually ask my patients is, “How many times a day do you eat?” This may seem silly to you, but these are two very different questions. It is essential that all weight-loss surgery patients begin to separate physical hunger from “head” hunger (emotional hunger). Tightening the band (or filling it) can help control physical hunger, but it won’t help with “head” hunger.

Portion Control

The band works by doing two things – controlling hunger and limiting portion size. To assess portion control, I ask patients to write down common foods they eat.

The first thing I look at is what type of foods are on the list. Are they all soft foods? This might indicate that solid foods are causing them pain because their band is too tight. Is there a wide variety of foods on the list or are there only three because those are the only three foods that will go down comfortably? If there is a solid protein listed, then I ask about the amount they can eat comfortably. Most band patients should be able to eat three to four ounces of solid protein without discomfort.

They should also be able to get in some vegetables or salad with their solid protein. In general, a band patient should be able to eat roughly 25 to 50 percent of the volume of food they could eat in one sitting prior to weight-loss surgery.

Weight-loss

A band patient who is “doing everything right” should lose approximately one to two pounds a week. Remember, with a band, it is definitely “slow and steady wins the race.” This can be a challenge for band patients as they need to be very patient as they are unlikely to reach their lowest weight until 18-24 months after weight-loss surgery.

Snacking between meals, consuming liquid calories and not exercising are common problems I often find when one of my band patients is not losing weight at a rate I would expect. For this patient, a fill is not going to help them and may lead to unintended complications.

Danger Signs

I ask each post-op patient I see, “So, how many times have you thrown up since the last time I saw you?” Generally, they’ll start laughing and say something like, “I didn’t, was I supposed to?” And the answer is…vomiting is never normal after weight-loss surgery! If a band patient (or any weight-loss surgery patient for that matter) is vomiting on a regular basis, then something is wrong and needs to be evaluated.

Here are some other symptoms that might mean your band is too tight or that there may be a problem with the band (slip, concentric dilation, etc):

– Significant and recurrent heartburn or reflux, especially at night

– Waking up at night coughing

– Pain when eating solid foods

– Pain or redness at your port sight

– Sudden loss of hunger or volume control

– Vomiting on a regular basis

Conclusion

I believe it is important for band patients to keep in mind that a band that is working well will only do two things:

- Control hunger

- Control portion size

By controlling these two key areas, band patients can begin to work on the challenging lifestyle changes they need to make to give them their best chance at creating long-term success after weight-loss surgery.

About the Author:

Lloyd Stegemann, MD, FASMBS, is a private practice bariatric surgeon with New Dimensions Weight Loss Surgery in San Antonio, TX. He is the driving force behind the Texas Weight Loss Surgery Summit and the formation of the Texas Asso ciation of Bariatric Surgeons. Dr. Stegemann is a member of the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery and the OAC National Board of Directors.

by OAC Staff Members Kendall Griffey and Michelle “Shelly” Vicari Winter 2024 In a world that often…

Read Articleby Rachel Engelhart, RD; Kelly Donahue, PhD; and Renu Mansukhani, MD Summer 2023 Welcome to the first…

Read ArticlePost-operative addiction is often overly simplified as transfer addiction or cross-addiction, assuming individuals “trade” compulsive eating for…

View Video