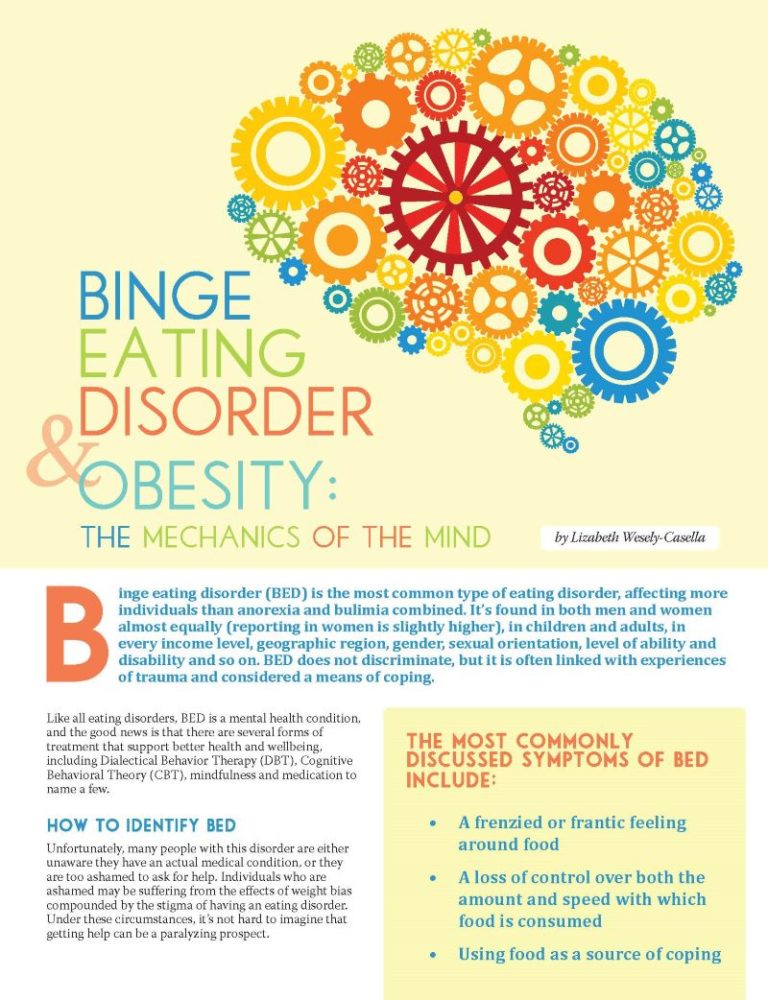

Binge Eating Disorder and Obesity

by Lizabeth Wesely-Casella

Summer 2015

Binge eating disorder (BED) is the most common type of eating disorder, affecting more individuals than anorexia and bulimia combined. It’s found in both men and women almost equally (reporting in women is slightly higher), in children and adults, in every income level, geographic region, gender, sexual orientation, level of ability and disability and so on. BED does not discriminate, but it is often linked with experiences of trauma and considered a means of coping.

Like all eating disorders, BED is a mental health condition, and the good news is that there are several forms of treatment that support better health and wellbeing, including Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT), Cognitive Behavioral Theory (CBT), mindfulness and medication to name a few.

How to Identify BED

Unfortunately, many people with this disorder are either unaware they have an actual medical condition, or they are too ashamed to ask for help. Individuals who are ashamed may be suffering from the effects of weight bias compounded by the stigma of having an eating disorder. Under these circumstances, it’s not hard to imagine that getting help can be a paralyzing prospect. The most commonly discussed symptoms of BED include:

- A frenzied or frantic feeling around food

- A loss of control over both the amount and speed with which food is consumed

- Using food as a source of coping

Usually these episodes are followed by humiliation, shame, a need for secrecy and isolation. For many, a binge is simply part of a cycle that includes anxiety, guilt, depression, shame and the need to sooth again, triggering another binge.

There are, however, many people who experience BED and who describe a wider, more nuanced spectrum of experiences. Binging doesn’t have to be frenzied. It can be grazing. It can be a small amount of food, but with accompanying shame and worry, or it can be a sense of not deserving nutrition and proper care because of body size, shape or previous binge behavior. BED also includes significant bouts of restriction, the only ‘compensatory’ behavior with regard to food use.

A binge episode is more than simply overeating. Most every person with resources to eat freely has experienced overeating or emotional eating. A typical binge for someone with BED is more like desperately trying to fill an unidentifiable need, with a drive to consume and the inability to sooth a deep wound. It isn’t simply additional helpings at Thanksgiving or that special delicious dinner that happens infrequently. BED is about a disordered relationship with both food and body, and it’s about mental health. It’s about coping mechanisms, about feelings, about shame and often, about reward. BED is a consistent companion for those who struggle, and it’s often a guiding voice when stress and anxiety become overwhelming.

Obesity and BED

Obesity can be one of the long-term effects of binge-eating, restrictive-eating and weight cycling. For those who live the at intersection of having BED and existing in a large body, the many layers of bias, stigma and size discrimination can be truly oppressive.

For people who experience negative social cues for obesity, consider the shame of being affected by this disease and having a shame-inducing secret about food and mental health. Consider the thought of never, even in private, feeling “good enough” for basic human needs like food, rest or companionship. That’s what an eating disorder, on top of social cues about a large body, sounds like.

Weight Bias and BED

Until recently, BED was among the least common eating disorders discussed. It was only in 2013 that the American Psychological Association added it to the DSM-5, and before that, many people simply didn’t have the information available to know there was such a disorder. There are many more reasons people don’t discuss BED — it’s closely associated with obesity and all of the shameful associations people make about body size.

Often, people with BED live in larger bodies and those bodies are frequently discounted as belonging to lazy, undisciplined and irresponsible people. People don’t often connect excess weight or obesity, to anything more substantial than ‘personal choice.’ For those in large bodies, comments, jokes, exclusion, discrimination, humiliation, and even violence are not unusual occurrences and may even happen on a daily basis. These are the painful, and often traumatic, experiences of people acting on weight bias.

Weight bias is unacceptable behavior that runs the spectrum from socially condoned to blatantly unlawful. There is an increasing awareness surrounding the very real harm that weight bias causes, and it’s being linked to protections and remedies, but not nearly fast enough.

People in large bodies, regardless of the reason, still do not have protections in most states from job loss due to discrimination. Additionally, many people in large bodies, as well as people with BED, are discriminated against in employee wellness programs if they do not meet health metrics such as body mass index (BMI) and weight-reduction benchmarks, or choose not to participate in the program at all. Often, the penalty is being forced to pay large financial sums in order to retain insurance coverage. This is unjust and discriminatory action based on a person’s size.

These forms of bias and discrimination add to the cultural belief that people in large bodies— people who suffer from obesity, people with BED and people with disabilities— are worth less than people in smaller bodies. That the work they perform has less importance, that they aren’t as disciplined or smart, or aren’t valuable employees and that they should be ashamed. The expression of those beliefs is bias, the internal consequence of which is stigma and all of this is social injustice. Beyond the workplace, weight bias, weight stigma and size discrimination happen in all areas of life.

Here are a few interesting facts that apply to anyone:

Family members are often reported as the most frequent sources of weight bias.

– Rudd Center on Food Policy & Obesity

“The likelihood of being bullied is 63 percent higher for a child affected by obesity compared to a thinner peer.”

– Rebecca Puhl, PhD, Rudd Center on Food Policy & Obesity

Because of the fear of being the “fat kid,” hospitalizations for eating disorders in kids under 10 years of age are on the rise – this includes BED.

– American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP)

Weight-based discrimination has been shown to lead to:

- Depression

- Poorer body image & self-esteem

- Decreased education/work outcomes

- Suicidal ideation

– Janet Latner, PhD

Weight-related teasing in adolescents is associated with:

- Lower self-esteem

- Depression

- Suicidal ideation in victims

– Dianne Neumark-Sztainer, PhD

“Children as young as three years old have been found to have internalized anti-fat attitudes.”

– Jennifer A. Harriger

Whether you have BED, or you are living in a large body, and you find yourself the target of size discrimination for any reason, you must understand that it is never acceptable or deserved. It’s worth noting that eating disorders have the highest mortality rate of all mental health diseases– a low estimate of the death rate is 10 percent, and that’s due in part to faulty reporting. If a person with an eating disorder succumbs to organ failure, often times the eating disorder is not listed as having caused the death even though it directly contributed.

People, in general, are bombarded by messages proclaiming the complete inadequacy of people with obesity, however, people with BED are often more sensitive to these messages which are directly connecting personal worth with body size and shape.

Treating BED

So if you have BED, what next? Should you seek treatment? Yes. Will it help these shaming messages have less power? Yes. Will it help teach coping skills and critical listening skills? Yes. Will it make me lose weight? That’s not the goal of treatment.

Unfortunately, the person in this position with BED is likely to assume that seeking treatment will result in significant weight-loss, and that’s simply not true. Though weight changes may occur, the point of seeking treatment is not to find another way to diet. Treatment is designed to address the underlying reasons for the food use: stress, poor coping skills, inability to prioritize self, body shame, low self-esteem and the repeated feelings of failure for having dieted and then weight cycled, having promised never to binge again only to succumb due to self-imposed pressure.

With a qualified treatment provider, ideally a BED specialist, individuals who are struggling learn that food is not the enemy, and that binging has less to do with food, and more to do with unmet needs. A therapist trained to treat BED will never suggest putting their client on a diet, because it is counterproductive to building the healthy food relationships that our bodies and minds need. A good BED therapist will assist in identifying emotions and disconnecting them from harmful behaviors.

If you are looking for a therapist or clinician, learn about the distinct certifications and credentials for eating disorder treatment providers, such as Certified Eating Disorders Specialists (CEDS), and Fellows of the Academy for Eating Disorders (FAED). Though your provider need not have those specific certifications, there are many amazing certified social workers, clinical social workers, licensed marriage and family therapists, psychologists and more.

When looking for the right type of therapist, familiarize yourself with what these treatment styles and subspecialties mean in order to narrow your search for what best fits your needs. Whenever you can, try to identify a therapist who has had significant time dealing with BED, weight stigma, trauma and shame.

Conclusion

The bottom line is that BED is a mental health issue that may impact weight and body size, and that treating the disorder may or may not change the shape of the body. The goal of treatment is to provide relief from the eating disorder, not to lose weight or ‘get in shape.’ When working on recovery, the body’s cues to eat when hungry and stop when satiated will fall in line, as will improved coping skills and interest in self-care. Those are the goals for treatment and those are the changes that truly improve daily life. To live a life of sound mental health and stability fulfills the promises that diets simply can’t. A healthy mind is not equivalent to a smaller size of pants.

If you feel as though you are out of control around food, that you feel fixated and isolated, that you are ashamed to eat around other people and that you hate your body, you may want to speak with your doctor about screening for binge eating disorder. If you need support finding a BED specialist who can help you, reach out to the Binge Eating Disorder Association (BEDA). BEDA is the sole organization focused on supporting people with BED and the providers who care for them. To learn more about BED or to become a BEDA member, please visit www.bedaonline.com or call 855-855-BEDA (2332).

About the Author:

Lizabeth Wesely-Casella is a weight stigma prevention advocate and a binge eating disorder (BED) expert. She works in Washington, DC as a coalition builder and speaker addressing the impact of size discrimination on communities and industry and the profound effect that weightism has on individuals with eating disorders, especially BED. As a speaker, Lizabeth blends science, humor, and cultural wisdom to engage her audience, creating a clear understanding of the disconnect between health and body shape and underscoring that shape and size do not reflect personal value or character. She also connects the dots between weight discrimination as a civil rights issue and the negative consequences to our economy, education, and workforce. Lizabeth’s advocacy has afforded her opportunities to speak in the Senate, on film, and in radio. Her advocacy work has positively influenced program design from college campuses to the White House including the Let’s Move! initiative. Lizabeth lives in Washington DC with her loving husband and delightfully spoiled dog, Noodle.

by Robyn Pashby, PhD Winter 2024 “No one is ever going to date you if you don’t…

Read Articleby Leslie M. Golden, MD, MPH, ABOM Diplomate Winter 2024 The journey to overcoming obesity is a…

Read ArticleDid you know that stress can have an impact on weight? Many people increase their food intake…

View Video