A Look at the Studies of the Risks of Bariatric Surgery

by Harvey Sugerman, MD

Winter 2006

There have been several recent articles in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) 1-3, that raised newspaper and television comments regarding the safety of weight-loss surgery, several of which were not justified.

Comparing the Numbers

The risk of death following weight-loss surgery in the non-Medicare studies 1,2 were much better than had previously been reported from Washington State in October 2004. The report by Santry et al 1 from the National In-patient Sample (NIS) noted a 0.1 to 0.2 percent in-patient mortality nationwide and the Zigmund et al study 2 noted an 0.18 percent in-patient mortality, and a 0.33 percent 30-day mortality for the State of California using the State’s Patient Discharge Database for gastric bypass. These are much lower than the previous report by Flum and Dellinger from Washington State, 4 which noted a 1.9 percent 30-day mortality following weight-loss surgery.

Like these recent reports from JAMA, the earlier Flum and Dellinger study received negative press coverage stating that the mortality of weight-loss surgery was much greater than single series studies suggested 5. Yet, the mortality in California is actually lower (0.1-0.2 percent vs. 0.5 percent in-patient risk of death) than many of the case series reports.

Why the discrepancy between the mortality in these two states? Could the better results be due to centers which perform greater numbers of bariatric surgeries and are therefore more proficient in their technique and patient care? Or, are there more ill Medicare and Medicaid patients in the Washington State database? Are the California surgeons operating on lower risk patients?

Obesity-Related Diseases

The Charlson Index was used to determine obesity-related illnesses in these reports. This measurement shows that 50-60 percent of the patients with severe obesity in these studies had no obesity-related diseases; whereas, it is clear that almost 100 percent of patients with severe obesity have one or more obesity-related conditions. Therefore, it is impossible to determine the degree of illness in these patients before their obesity surgery in order to compare these reports. Collection of this information is extremely important and will be undertaken by the American Society for Bariatric Surgery (ASBS) Centers of Excellence (COE) program.

Risk for Medicare Patients

The study by Flum et al 3 regarding the risk of death in Medicare patients found a much higher mortality in these patients than previously reported for bariatric surgical procedures 5. This is no surprise, since 90 percent of patients who undergo weight-loss surgery with Medicare coverage are social security disabled and are under the age of 65. These are the sickest patients, almost certainly a consequence of their obesity, and they therefore have the greatest risk of surgery.

It may cost more for these patients to undergo surgery than the surgeon or the hospital are reimbursed for, which may be one of the reasons that they are under-represented in the Santry et al study 2. In fact, according to MedPAR data, the age adjusted risk of death after laparoscopic and open cholecystectomy (gallbladder surgery) from 2001 to 2003 were higher than the risk of gastric bypass surgery. Of greater concern, is the increased risk of death with obesity surgery noted by Flum et al in those more than 65 years of age. Several studies noticed an increased mortality associated with age 6-8. However, the data may not be as grim as the press reported. The Flum et al study noted that those centers who have the highest number of Medicare cases (and it may be presumed the greatest number of bariatric procedures regardless of status) had a 1.1 percent 30-day mortality rate in those more than 65 years of age, a very reasonable number in this age group. In a series study of patients more than 60 years of age, 19 of which were more than 65 years of age, there were no deaths at one year after surgery 9. In another series of 27 patients, 13 had a laparoscopic gastric bypass and were more than 65 years of age 10.

Risk after Surgery

Lastly, there are serious concerns regarding the study by Zigmund et al, which noted a marked increase in hospital visits in the three years after weight-loss surgery as compared to the three years preceding weight-loss surgery 3. There are three groups in this study which warrant further comment and account for more than 50 percent of the hospital visits after surgery.

Early readmissions for complications related to nausea and vomiting (15-20 percent) are probably associated with pressures from health insurance companies for early hospital discharge. The second group (15-20 percent) are those who are readmitted for incision related problems (hernias and wound infections) and are almost certainly related to the high frequency of open weight-loss surgery during the time period of this study. These complications have been virtually eliminated with the currently laparoscopic approach. The third group (another 20-30 percent) is for patients who have undergone plastic surgical or orthopedic procedures following their weight-loss surgery. The orthopedic operations, such as hip and knee replacement, are more likely to be successful following a surgically induced weight-loss. Lastly, the costly and life-threatening readmissions for serious medical conditions, such as chest pain, coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, obstructive lung disease and cellulitis, were all decreased following weight-loss surgery. Readmissions for life-threatening complications of the surgery (leak, internal hernia) are of concern, but represent a minority of the cases. Again, this study noted that surgery performed at a low volume medical center was more likely to result in hospital readmissions.

ASBS Centers of Excellence

These studies confirm other reports that surgeons who perform a significant number of cases at hospital centers with a dedicated staff and appropriate numbers of surgical procedures have noted much lower risks of deaths and complications. We recommend that patients who undergo obesity surgery have their operation at an ASBS Center of Excellence, which mandates these centers to perform more than 125 cases a year with surgeons who perform more than 50 cases a year and have processes and facilities designed to optimize the care of the bariatric patient. (To learn more about the Centers of Excellence program, see page 14.) Outcomes of these Centers will be collected on an annual basis and the Center will have to be re-designated one to three years after the initial approval.

There is no other effective treatment for patients with severe obesity. Bariatric surgery performed in an approved high volume Center of Excellence can provide profound improvements in obesity co-morbidities and quality of life, at a reasonable cost and with a very low risk of death and complications.

About the Author:

Harvey Sugerman, MD, is a retired bariatric surgeon. Formerly, he was Chief of the General Surgery/Trauma Division at Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond, VA. He is the immediate Past-President of the American Society for Bariatric Surgery and was a non-voting member of the Medicare Coverage Assessment Committee on Bariatric Surgery. He is currently the Chairman of the Bariatric Surgery Review Committee which evaluates applications for Bariatric Surgery Centers of Excellence under contract to the American Society for Bariatric Surgery. Dr. Sugerman is a member of the Obesity Action Coalition.

References:

- Santry HP, Gillen DI, Lauderdale DS. Trends in bariatric surgical procedures. JAMA 2005;294:1909-1917.

- Zingmund DS, McGory ML, Ko CY. Hospitalization before and after gastric bypass surgery. JAMA 2005;294:1918-1924.

- Flum DR , Salem L, Elrod JAB, Dellinger EP, Cheadle A, Chan L. Early mortality among Medicare beneficiaries undergoing bariatric surgical procedures. JAMA 2005;294:1903-1908.

- Flum DR , Dellinger EP. Impact of gastric bypass operation on survival: a population-based survey. J Am Coll Surg 2004;199:543-551.

- Buchwald H, Avidor Y, Braunwald E, et al. Bariatric surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2004;292:1724-1737.

- Gonzalez R, Lin E, Mattar SG, Venkatesh KR, Smith CD. Gastric bypass in morbidly obese patients 50 years or older. Am Surg 2003:69:547-553.

- Livingston EH, Huerta S, Arthur D, Lee S, DeShields S, Heber D. Male gender is a predictor of morbidity and age a predictor of mortality for patients undergoing gastric bypass surgery. Ann Surg 2002;236:576-582.

- Soso JL, Pombo H, Pallavicini H, Ruiz-Rodriguez M. Laparoscopic gastric bypass beyond age 60. Obes Surg 2004;14:1398-1401.

- Sugerman HJ, DeMaria EJ, Kellum JM, Sugerman EL, Meador JG, Wolfe LG. Effects of bariatric surgery in older patients. Ann Surg 2004;240:243-247.

- Quebbemann B, Engstrom D, Siegfried T, Garner K, Dallal R. Bariatric surgery in patients older than 65 years is safe and effective. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2005;1:389-392.

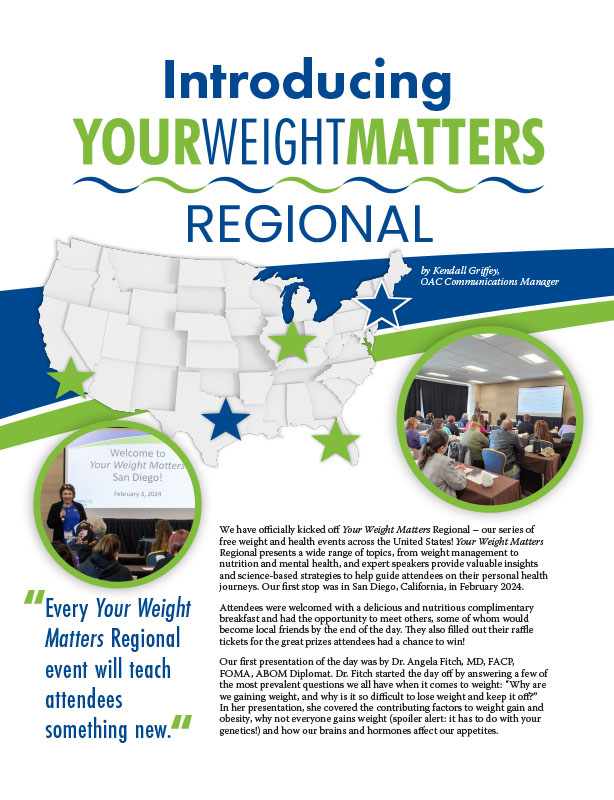

by Kendall Griffey, OAC Communications Manager Spring 2024 We have officially kicked off Your Weight Matters Regional…

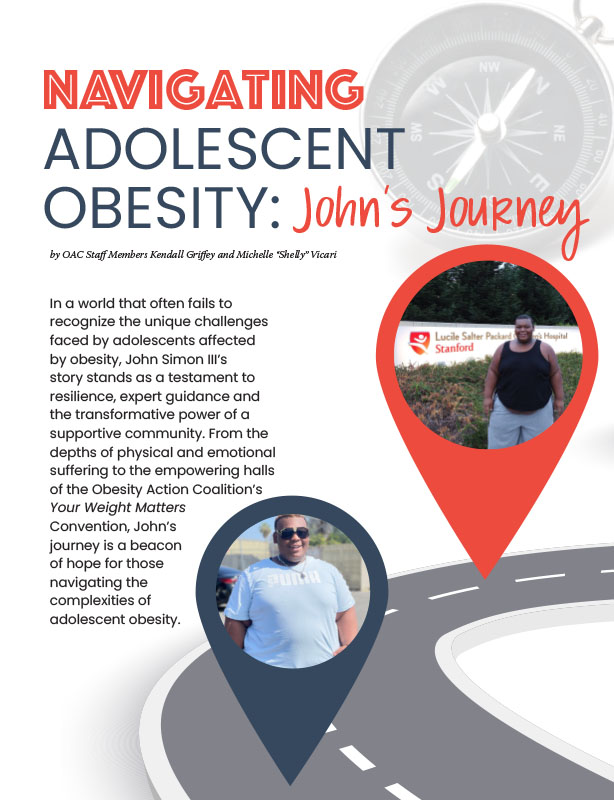

Read Articleby OAC Staff Members Kendall Griffey and Michelle “Shelly” Vicari Winter 2024 In a world that often…

Read Articleby Sarah Ro, MD; and Young Whang, MD, PhD Fall 2023 Mary, a postmenopausal woman with a…

Read Article