Sports Drinks – They’re healthy, right?

by Nadia Boulghassoul-Pietrzykowska, MD, FACP

Summer 2013

If you go down the beverage aisle in any grocery store today, you’re bound to find a wide variety of sports drinks, all promising things like “power,” “hydration,” “energy bursts” and much more. Quite often, this is crafty marketing on the part of the sports drink manufacturers; however, the main question on your mind in the sea of “promises” should be, “Are these sports drinks healthy?” Well, let’s find out.

Sports Drinks

Sports drinks are sugar sweetened beverages containing water, sodium, potassium, artificial color and flavorings. They are recommended for athletes that perform intense exercise lasting more than 60 minutes according to the American College of Sports Medicine. For such intense exercise, they help provide energy and prevent dehydration. Sports drinks typically contain water and electrolytes (usually sodium and potassium) for rehydration, and carbohydrates (as sugars) for energy.

They were invented in the 1960s to replenish fluid and provide extra fuel for intense sporting activity of a long duration. From the physiological point of view, there’s a benefit in having carbohydrates for sustained intense exercise of more than 60 minutes. This is because when we start exercising, our muscles initially use their stores of carbohydrate for fuel, but these stores become depleted after about 90 minutes. Our muscles then start to become more reliant on fat burning for fuel. This isn’t as efficient as burning carbohydrates, so our pace is slowed. The intake of worthwhile amounts of carbohydrate from a source during exercise, such as a sports drink, provides an alternative or additional source of fuel allowing carbohydrates to continue to be ‘burned’ at the higher levels needed to sustain the athlete’s optimal pace.

For ordinary people who play sports more casually, there’s no need for them because the fluid requirements can be met by water and generally we do not sweat enough to lose excessive amounts of electrolytes. In addition, if we are exercising to lose weight, drinking a sports drink may mean that we need to spend an extra half hour or more at the gym. This is why, for less intense physical activity, water is considered to be the best hydrator.

A national survey of high school students showed that less than 20 percent of students reach a high level of physical exertion, therefore, much of the youth drinks these beverages without a good reason and to the detriment of their health.

Extra Calories

When used outside of the context of significant physical exertion, these drinks provide large amounts of unnecessary sugar and sodium. Many of them are available in 32 ounce bottles and contain 56 grams of sugar, which is the equivalent of 14 teaspoons of sugar. This is above the recommended maximum amount for a whole day. Studies have shown that these beverages were linked to weight gain in both adults and children.

In addition, a large sports drink bottle contains about 480 mg of sodium, which is one fifth of the maximum daily allowance as recommended by the American Heart Association. This is significant because increased sodium consumption may raise blood pressure, which in turn may increase the risk of stroke and heart disease.

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) states that children consuming these beverages are at increased risk for obesity. Therefore, the recommendation is to avoid consuming them and children should drink water before, during and after exercise. AAP also adds that small amounts of these drinks can be given to children exercising in hot and humid conditions for more than one hour.

In addition, scientists have shown that individuals consuming sports drinks on a regular basis have eroded tooth enamel. Many of these products are based on acidic fruits and the amount of enamel lost was significant. Dental erosion is the most common chronic disease of children ages 5 to 17 and it has been recently recognized as a dental health problem.

Sales Continue to Increase

Despite having no benefit for most, the sales of these drinks skyrocketed in recent years. Furthermore, as the consumption of carbonated soft drinks in schools has finally decreased, at the same time, the purchase of sports drinks by youth increased by 70 percent. This is mostly due to the fact that they are marketed as healthy drinks; however, in reality, most of them are nothing but sugar sweetened beverages with many unhealthy features.

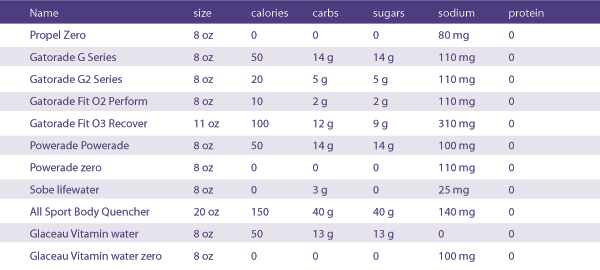

Even when it comes to lower-calorie versions of the drinks, consumers should still be certain they know what constitutes a “serving,” as well as how many servings are in an individual bottle. A particular low-calorie sports drink, for example, might advertise that it has only 20 calories per 8-ounce serving, but have 2.5 servings in a bottle. That’s still a savings instead of the full-calorie version of the beverage, which may have 80 calories per serving. But it’s not zero.

When you’re deciding whether to choose water or a sports drink, here are some guidelines:

Use water when:

-

-

- Exercising to lose weight

- Exercising for an hour or less

-

Consider using a sports drink when:

-

-

- Doing intense sustained exercise for 90 minutes or more

- The outcome of a competition is important to you and you need to perform at your best. Using small amounts every 10-15 minutes can make you feel like working harder.

-

Also, sports drinks should not be confused with energy drinks. These have also a lot of caffeine and contain various herbs and supplements and make health claims not approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

Conclusion

When you decide to choose a sports drink, be aware that they are not created equal. Below, please find a table which details some of the most popular sports drinks:

Also, If you want to try to spruce up plain water, a spritz of lemon juice or lime juice, or a packet of a very low-calorie drink such as Crystal Light, can make things more palatable And with all this said, let’s reconnect with the oldest beverage known to mankind – water.

About the Author:

Nadia Boulghassoul-Pietrzykowska, MD, FACP, is a board certified physician nutrition specialist with residency training in internal medicine and subspecialty training in bariatric medicine and nutrition.

by Sarah Muntel, RD Spring 2024 Spring has sprung, bringing sunnier and warmer days! For many, this…

Read Articleby Michelle “Shelly” Vicari Winter 2024 Winter has arrived! Don’t allow the chilly and damp weather to…

Read Articleby Kendall Griffey, OAC Communications Coordinator Winter 2024 The Obesity Action Coalition’s 12th annual Your Weight Matters…

Read Article