Dear Doctor: What Does BMI Percentile Mean for My Child?

by Joseph Skelton, MD, MS; and Callie Brown, MD, MPH

Summer 2022

As pediatricians, we frequently get asked by parents, “what should my child weigh?” A common saying in pediatrics is that “kids are not little adults,” and this is particularly important when considering a child’s weight. Children are constantly growing and changing, and they go through growth spurts at different times. Throughout childhood and adolescence, their level of adiposity, or how much fat-to-lean mass they have, changes as they get older. Most children should gain weight as they get older – they are growing muscles and bones, which weigh a lot! So it is nearly impossible to tell a parent what their child “should” weigh. Talking about a child’s growth, height and weight involves nuance and is more complicated than evaluating an adult’s weight status.

Growth Charts

Similar to adults, we do use body mass index, or BMI, to take height and weight into account together. It’s the same calculation for children and adults – weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared:

BMI=kg/m (squared)

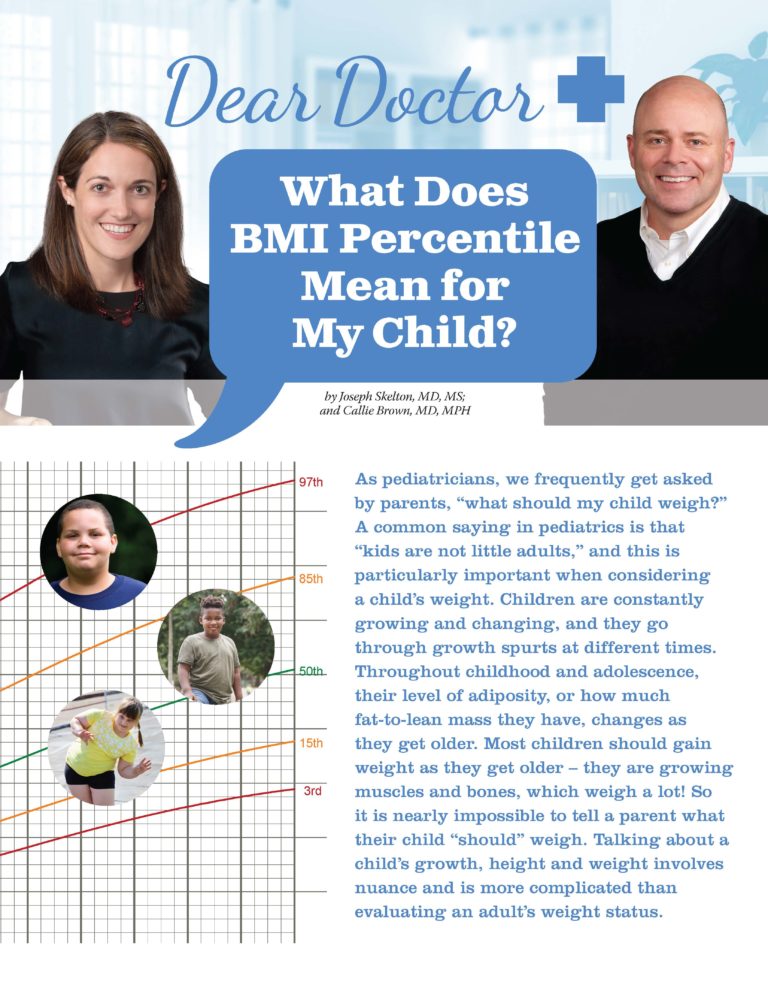

For children, we don’t look at raw BMI (a number usually between 18-40) but instead, we look at BMI percentiles, taking into account the child’s sex and age. So like all things pediatric, we use the growth chart! Growth charts have been in use since the early 1900s, but previous versions had plenty of problems – they didn’t include preschool-aged children and didn’t represent all children in the U.S., particularly those from traditionally underrepresented backgrounds and different areas of the country.

The most widely used growth charts from the 1940s to the 1970s were based on measurements of white children in Iowa and Boston. In 1977, new growth charts were introduced based on more representative data and then updated again in 2000. Most importantly, the 2000 growth charts included information on BMI.

Nowadays, it’s usually not a paper growth chart that we look at with families, as BMI percentiles are automatically calculated in the electronic health record or an online calculator.

BMI Percentiles

As kids are constantly growing taller and their bodies are changing, we cannot use the same BMI cut-offs for adults. For example, a BMI of 22 in adults falls into the “healthy weight” category, though a BMI of 22 in a 6-year-old child would be in the obesity range. This is because of the significant differences in the range of heights and weights that a child of 6 years of age can have. So for children, the number on a scale is not the only important factor when it comes to their weight status, but also what their height, age and sex are. The calculation of this BMI percentile can be plotted on a growth chart to give a sense of where they fall compared to other children of the same sex and age. In general, the percentiles break down to:

- Less than the 5th percentile for age and sex: This is considered underweight, which could potentially be worrisome if the child is not receiving adequate nutrition.

- 5th to less than the 85th percentile: This is what is considered a healthy weight for most children.

- 85th to less than the 95th percentile: This is considered overweight. Unlike adults, where this range is where we start to see an increase in some health risks in children, this range means the child is at an increased risk of crossing over into the obesity category, either in childhood or later in adulthood.

- 95th percentile or higher: This is considered obesity. This is where we begin to be concerned about children developing health risks because of their weight, such as prediabetes, hypertension or high cholesterol. Also, this category means that the child has an increased risk of continued obesity into adulthood.

Evaluating Your Child’s Growth

More important than evaluating a single point in time (or one point on the growth chart) is evaluating the trend of your child’s growth and looking at how their BMI percentiles have changed.

For example, as pediatricians, we are much less concerned about a child who has been at the 85th percentile for her entire life compared to a child who is now in the 85th percentile but had previously been at the 30th percentile and has had a steady and steep increase in her weight over the past two years.

Any time there are significant changes in growth trajectories, either up or down, we want to pay close attention and figure out what is changing. It is also important to note that growth is not linear. While the curves on the growth chart make very nice lines, in reality, kids’ heights and weights increase in fits and spurts (and not always together!). That is why paying attention to the trend over time is the most important aspect of looking at a growth chart.

It is extremely important to remember that BMI is a screening tool. It doesn’t peer below the skin to say how much lean muscle mass or adipose tissue a child has. It cannot determine a child’s health, although it may tell us that a child is at risk of developing later obesity or certain health problems related to weight.

For example, a teenage male aged 16 years with a BMI percentile in the obesity range has a much higher risk of developing type 2 diabetes (as a teenager or later as an adult) than a 6-year-old boy whose BMI percentile is in the healthy weight category. BMI also doesn’t tell us the overall health status of a child. So while it’s important, remember it is a screening tool and a jumping-off point to discuss health habits and prevention.

What Does BMI Percentile Mean for my Child?

First of all, remember, BMI is a screening tool. DO NOT PANIC. Talk to your child’s provider, look at the growth charts together, and take everything into account. Consider your family’s nutrition and activity habits, family medical history, and how their weight status has been over the past few years. Most importantly, you don’t want your child to feel that their weight means something about their self-worth or who they are. Nor should you take this as a judgment of you as a parent.

We discourage providers and families from talking about “weight” with their child, although it is important to directly address issues such as bullying that could be occurring. Instead, focus on establishing healthy family habits, particularly those habits that involve the family spending time together preparing and eating meals or doing fun activities together. BMI percentiles are a screening tool that is just one part of the big picture of doing what is best for your family’s health.

About the Authors:

Joseph Skelton, MD, MS, is a board-certified pediatrician and obesity medicine specialist. He has a particular interest in working with entire families to change behavior, as well as working with community organizations that have the same goals. He is the founder and director of Brenner FIT® (Families In Training), a family-based pediatric obesity program that is active in clinical care, research, education and community outreach.

Callie Brown, MD, MPH, is an assistant professor of Pediatrics and Epidemiology and Prevention at Wake Forest School of Medicine. Dr. Brown is a board-certified general pediatrician and NIH-funded clinical researcher with expertise in obesity prevention and treatment in early childhood, specifically related to picky eating, parental concern about their child’s growth, and social determinants of health such as food insecurity. Her research focuses on evaluating how parental feeding practices are associated with child stress and a child’s later risk of obesity.

by Sarah Muntel, RD Spring 2024 Spring has sprung, bringing sunnier and warmer days! For many, this…

Read Articleby Robyn Pashby, PhD Winter 2024 “No one is ever going to date you if you don’t…

Read Articleby Michelle “Shelly” Vicari Winter 2024 Winter has arrived! Don’t allow the chilly and damp weather to…

Read Article