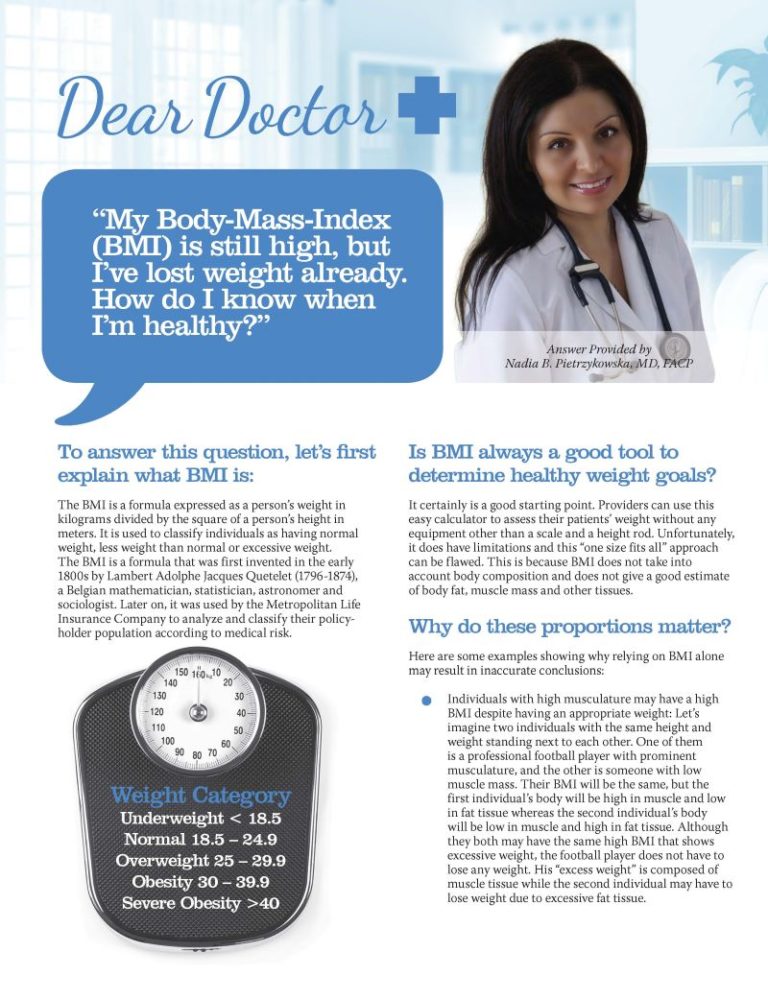

Dear Doctor: My Body-Mass-Index (BMI) is still high, but I’ve lost weight already. How do I know when I’m healthy?

Answer provided by Nadia B. Pietrzykowska, MD, FACP

Fall 2016

To answer this question, let’s first explain what BMI is:

BMI, or Body Mass Index, is a formula that calculates a person’s weight in kilograms divided by the square of their height in meters. It’s commonly used to categorize individuals as having a healthy weight, being underweight, or having excess weight.

BMI was initially devised in the early 1800’s by Lambert Adolphe Jacques Quetelet (1796-1874), a Belgian mathematician, statistician, astronomer and sociologist. It was later adopted by the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company to assess the medical risk of their policyholders.

Is BMI always a reliable tool to determine healthy weight goals?

While BMI is a helpful starting point, it does have its limitations. Healthcare providers can use this simple calculation to gain insights into their child’s health status without any equipment other than a scale and a height rod. Unfortunately, the “one size fits all” approach that BMI uses is flawed because it doesn’t consider factors such as body composition, muscle mass and other tissues, nor does it provide an accurate estimate of body fat.

Why do these considerations matter?

Here are some examples illustrating why relying solely on BMI may result in inaccurate conclusions:

- High Muscle Mass: Individuals with high musculature may have a high BMI despite being healthy. Consider two individuals of the same height and weight standing next to each other. One is a professional football player with well-defined muscles, while the other has low muscle mass. Despite having the same BMI, the football player’s excess weight is mostly muscle, whereas the second individual carries more fat. It’s crucial to differentiate between these two scenarios, as the second individual has a higher risk of obesity and weight-related health issues.

- Thin-Built Individuals: Some individuals with a naturally thin build may gain unhealthy amounts of fat faster than their BMI can indicate. These individuals have a naturally low muscle mass. Their BMI might still fall within the normal range, but their fat proportion may be increasing into an unhealthy zone. Early weight-loss interventions may be necessary.

- Older Adults: BMI classifications may not always apply to individuals above the age of 65. As people age, they often lose muscle mass while gaining fat and tend to follow the model of the thin-built individuals described above. This can result in an increase in fat tissue before BMI reflects the change. That said, some studies suggest that a slightly elevated BMI may be healthier for older adults. More research is needed to determine optimal weight goals for older adults.

- Individuals with Weight-Related Conditions: The presence of diseases like Type 2 Diabetes, hypertension and high cholesterol should take precedence over BMI information. This means that if an individual has one or more of these conditions, it is crucial to work on losing weight – especially if these conditions appear or worsen with weight gain. While it may be reasonable for someone with obesity who has no other medical conditions to remain at an overweight BMI, further weight-loss should be recommended to individuals with weight-related medical conditions. Additionally, the presence of pre-disease, specifically prediabetes, should prompt weight-loss efforts to attempt reversing it. Prediabetes is a condition where certain blood glucose parameters are above the normal range but not quite yet in the diabetic range. Prediabetes can often be reversed with weight-loss and lifestyle changes.

- Ethnic Considerations: Commonly referred-to BMI thresholds do not apply to certain ethnic groups. For individuals of Asian descent, for example, the risk of cardiometabolic diseases increases with lower BMI values when compared to Caucasian individuals. This means that a BMI considered normal according to the standard chart may be overweight for these patients. Relying on BMI alone may underestimate weight excess.

For these reasons and others, while having an elevated BMI increases your risk for overweight and obesity, only a healthcare provider should make the final determination.

Since BMI is not always accurate, what other tools could be helpful?

Waist circumference:

While it is a very simple measurement, waist circumference can provide useful information. In general, excessive fat tissue located in the abdomen is considered to be harmful. To decrease cardiometabolic risk (the risk of developing certain diseases such as heart disease, stroke, diabetes, high cholesterol, etc.), an optimal waist circumference should be below 35 inches in women and 40 inches in men. When it’s higher than these values, waist circumference can contribute to Metabolic Syndrome. This is a constellation of physical and laboratory findings that increases one’s risk of developing cardiometabolic diseases like the ones mentioned earlier. Measuring weight circumference can supply valuable information that will help healthcare providers treat their patients appropriately.

Hip-to-waist ratio:

In addition to a waist measurement, a hip width measurement should be made. When the circumference of the waist is divided by the circumference of the hips, a ratio will result. A ratio of less than 0.9 for men and less than 0.8 for women is considered healthy. Higher ratios predispose to many cardiometabolic diseases as described earlier. For example, an apple-shaped woman (higher waist/hip ratio and more fat tissue in the abdomen) with a BMI of 40 may be at a higher risk of developing diabetes than a pear-shaped woman (lower waist/hip ratio and more fat tissue in the hip area) with the same BMI.

As a result, a person with excessive weight and an apple-shaped body may have to be more concerned about their weight than someone with a pear-shaped body, despite them both having the same BMI.

Body fat and body composition measurements:

There are several ways to estimate or measure body fat. Skin calipers that measure skin folds can help determine body fat content and provide helpful information regarding the need for weight-loss. More complex measures can also be achieved by machines that determine body composition. Some of them may be available in your health provider’s office, and others are mostly used by scientists for research. These machines can, with varying accuracy, estimate ad measure body composition and the proportion of tissues: fat tissue, musculature, other lean tissues and water. They can be helpful during weight-loss to guide treatment and build a program with an adequate diet and exercise regimen.

These additional tools provide useful information that helps determine whether an individual is at a healthy weight or if weight-loss is needed.

Other Factors to Consider When Determining Weight-loss Goals

In addition to these factors, two more should be taken into consideration when trying to determine weight-loss goals:

- Basal metabolic rate (metabolism) and its fluctuations that affect weight-loss and weight maintenance: Metabolism varies from one individual to another and is affected by many internal and external factors. It is also affected by the process of weight-loss itself. Although much is to be investigated further in this field, being cognizant of variations in the metabolic rate of individuals during and after weight-loss is important because it affects both weight-loss and weight maintenance.

- Quality of life improves with weight-loss. Although more subtle than and not as obvious as some of the disease states we mentioned earlier in this article, having obesity and excess weight should not be underestimated. Fatigue, chronic pain and quality of life in general can improve with weight-loss and act as goals to encourage individuals to live life to its fullest potential.

Conclusion

In summary, it is important to understand that weight-loss goals should not be exclusively determined by a number on a scale. In this article, several different factors were described that can affect and guide one’s weight-loss goals.

It’s also important to add that several other factors will determine how much weight someone cannot only lose, but maintain as well. Complex processes involving the brain, several body systems, hormones and behavioral factors will determine the extent of weight-loss and long-term weight maintenance. Although much is still to be researched and understood, this information should not go underestimated.

About the Author:

Nadia B. Pietrzykowska, MD, FACP, is a Board Certified Obesity Medicine Specialist, Nutrition Physician Specialist and Health Coach with a primary specialty in Internal Medicine. She is the Founder and Medical Director of “Weight & Life MD,” a Center for medical weight management located in Ewing, NJ. She promotes the use of evidence-based methods for obesity treatment as well as cutting edge science intertwined with a holistic approach. She contributes to the Education Committee of the OAC and writes for its publications.

Post-operative addiction is often overly simplified as transfer addiction or cross-addiction, assuming individuals “trade” compulsive eating for…

View VideoIt can be challenging to find the right help for your child who has obesity. The first…

View VideoConsidering a robotic surgery procedure? In this Health Talk, you’ll hear from bariatric surgeon Walter Medlin, MD,…

View Video